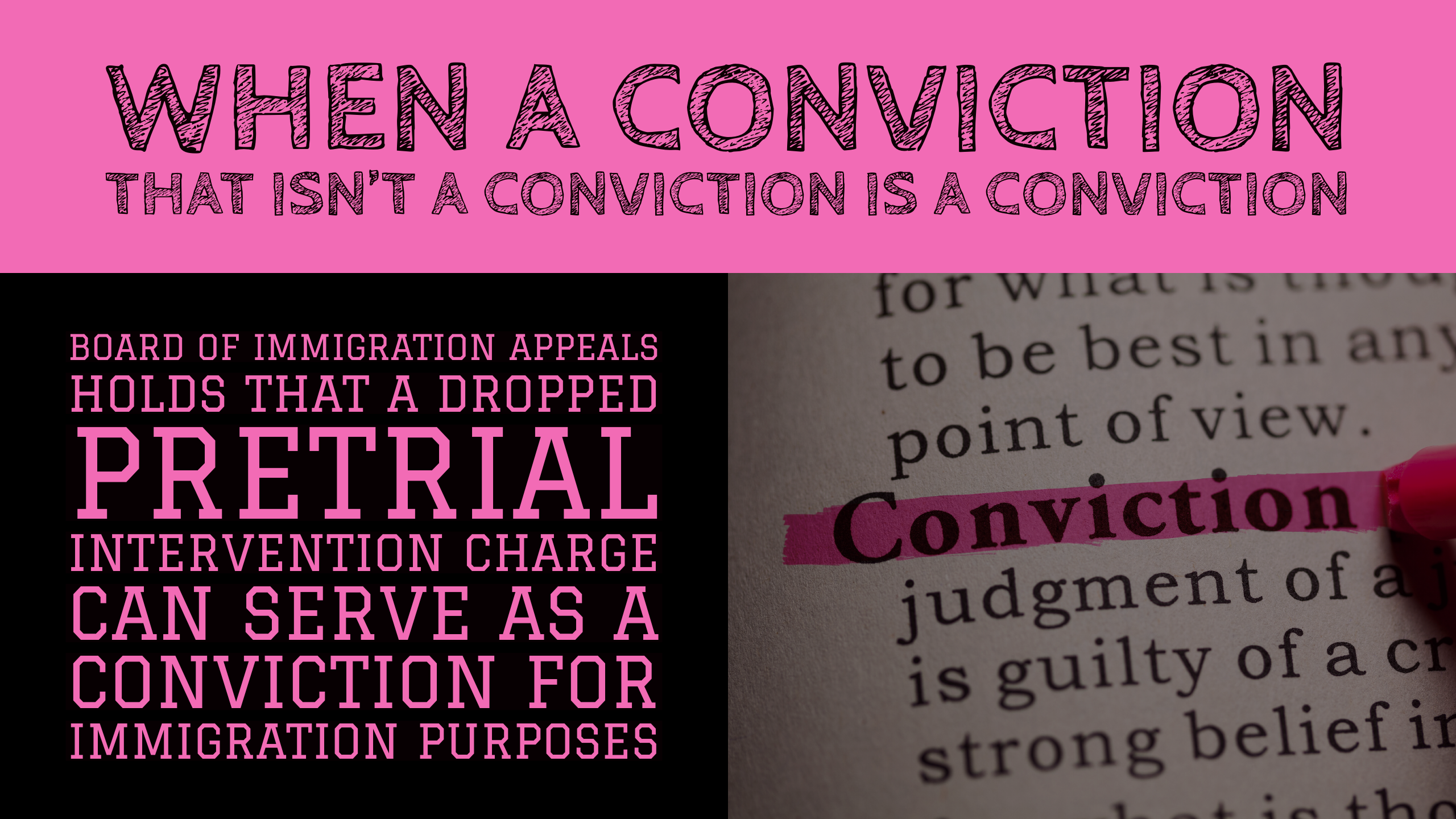

Consider this: You are a Lawful Permanent Resident who has lived in the United States for nearly your entire life. You have always been in the United States legally. One day, you get arrested for a crime you did not commit. Or maybe you did violate the law, but it was a very minor charge and you have never been in trouble before. Like so many United States citizens in the same situation, you are offered a pretrial intervention program. That is, the prosecutor diverts your case from the court system, has you perform some community service, pay some fines, maybe take a class, and if you complete all of the requirements, they drop the charges. Under the laws of the State of Florida, you would even be able to get the charge expunged from your record. After all, the law in this land of opportunity is set up to give people second chances when they make a mistake. So, you enter the pretrial diversion program, do everything you were asked to do, successfully complete it, and the charges are dropped. All is well, right?

Well, not according to the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA). In a recent decision, the Board of Immigration Appeals held that even if a case is referred to a pretrial diversion program and ultimately dropped, it can serve as a conviction for immigration purposes and be used as the basis for deportation. What? How can that be? Here is the thought process:

What is the definition of a “conviction” for immigration purposes?

Florida Immigration Lawyer Blog

Florida Immigration Lawyer Blog

As an immigration attorney, when I talk to my immigration clients about their future, the first thing I tell them is to become a United States citizen as fast as they can, if they want to spend the rest of their life in the United States. I tell them to run, not walk, to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services Office to file an N-400 Application to naturalize. I pick up the bulky Immigration and Nationality Act and tell them they can have a bonfire and burn that book after they naturalize, because the Immigration and Nationality Act no longer applies to them. They will become full fledged United States citizens with all the bells and whistles. But with everything in life, especially in the law, there are exceptions. And one of those exceptions is through a process called denaturalization.

As an immigration attorney, when I talk to my immigration clients about their future, the first thing I tell them is to become a United States citizen as fast as they can, if they want to spend the rest of their life in the United States. I tell them to run, not walk, to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services Office to file an N-400 Application to naturalize. I pick up the bulky Immigration and Nationality Act and tell them they can have a bonfire and burn that book after they naturalize, because the Immigration and Nationality Act no longer applies to them. They will become full fledged United States citizens with all the bells and whistles. But with everything in life, especially in the law, there are exceptions. And one of those exceptions is through a process called denaturalization.

A person in deportation proceedings is eligible for a fraud waiver even when they are not specifically charged with a fraud based basis of inadmissibility. The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals recently held that the Board of Immigration Appeals erred in finding that Mr. Acquaah was ineligible for a 237(a)(1)(H) fraud waiver because he was charged with having his permanent resident status terminated, rather than being charged with being deportable for committing fraud.

A person in deportation proceedings is eligible for a fraud waiver even when they are not specifically charged with a fraud based basis of inadmissibility. The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals recently held that the Board of Immigration Appeals erred in finding that Mr. Acquaah was ineligible for a 237(a)(1)(H) fraud waiver because he was charged with having his permanent resident status terminated, rather than being charged with being deportable for committing fraud.